Rooted in History: Zea Mays

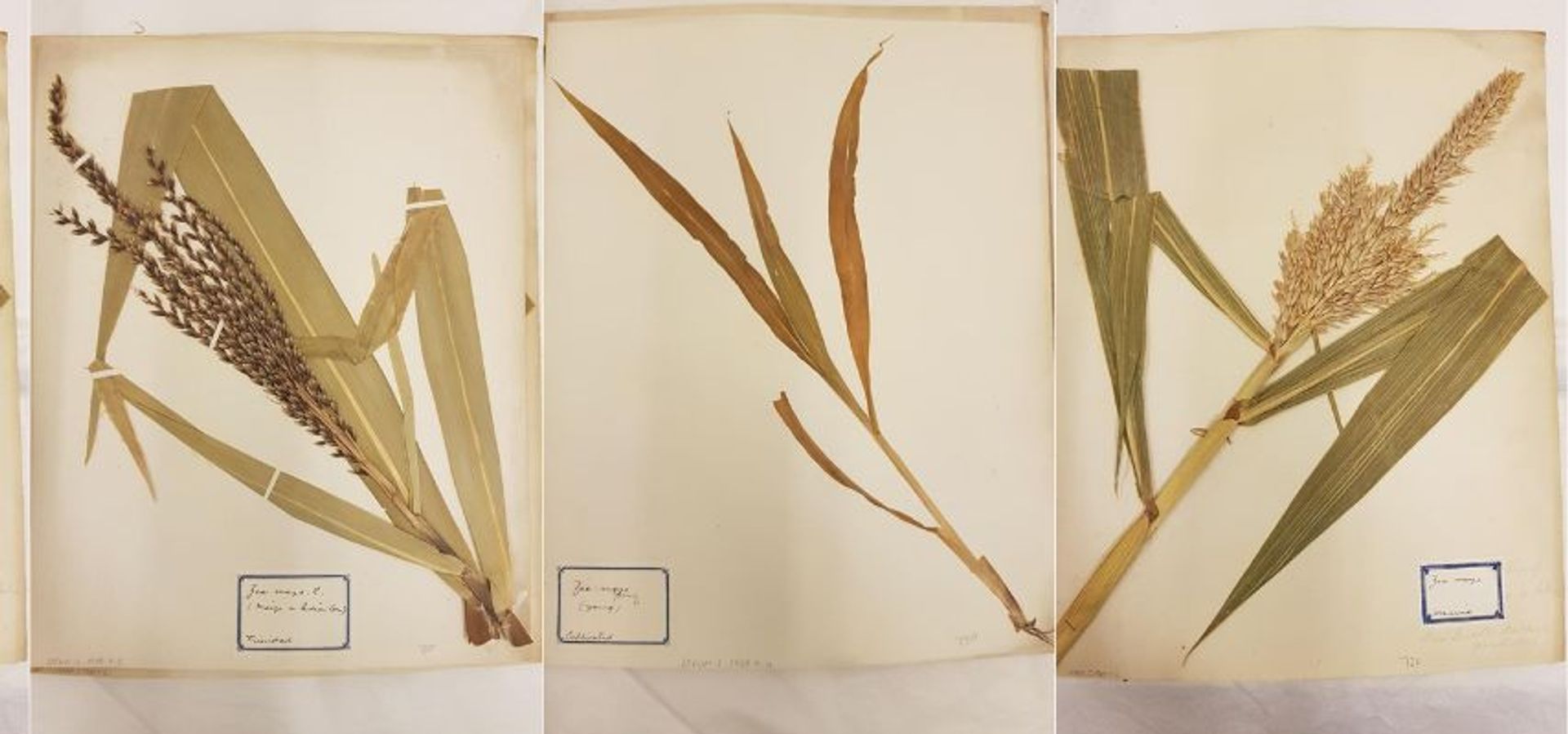

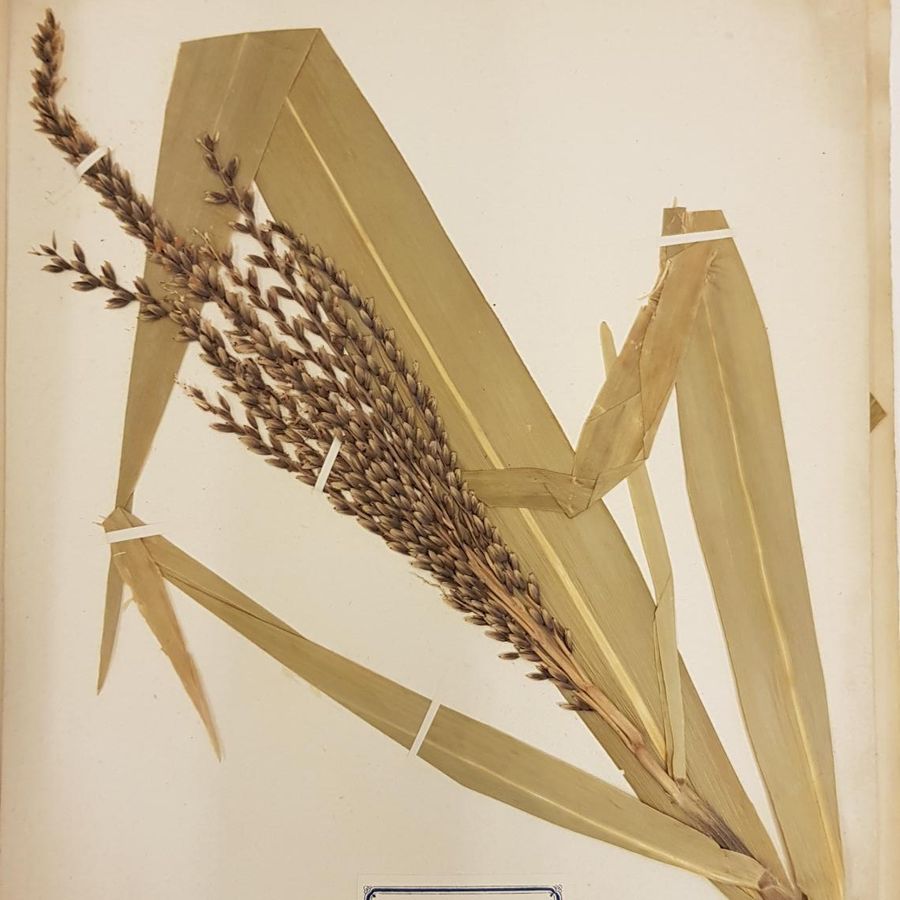

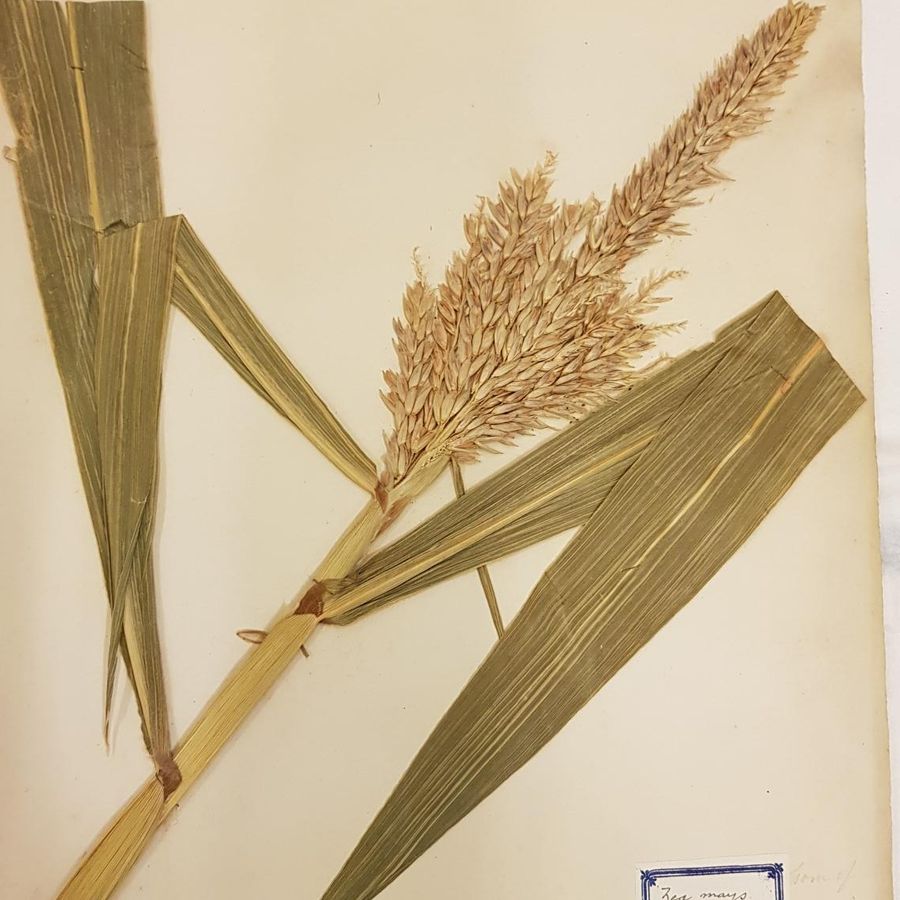

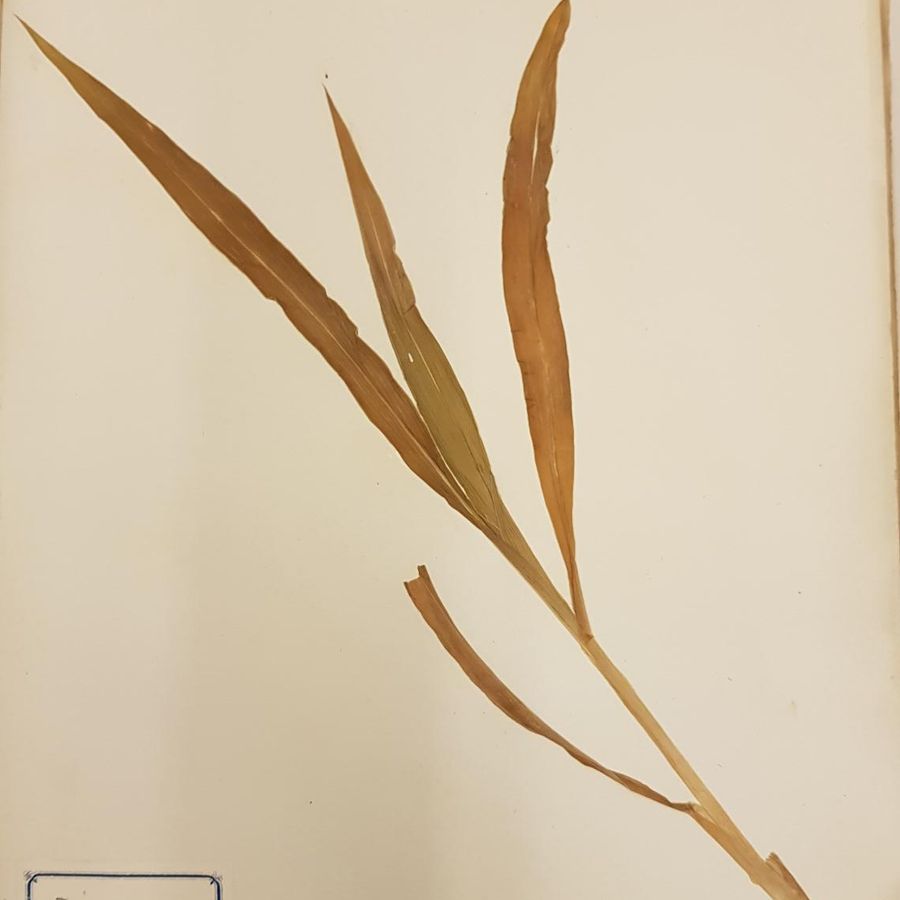

Whenever I think of corn, I immediately think of popcorn and movies and underwhelming corn on the cobs at barbecues (British summer weather permitting!). A simple Google search on this humble grain leads to the realisation that it is omnipresent. So, in addition to its being significant in the food chain for humans and animals alike (along with rice and wheat), corn and its derivatives have found their way into industrial, chemical and pharmaceutical processes – from soaps, adhesives, paints, dyes, and lubricants to dry-cell batteries, fuel ethanol, solvents, binding agents in medication, and fermentation in the alcohol industry to name but a few. Leeds has a number of herbaria specimens of corn/maize from around the world in its collection – some dated as further back as 1842 and from as far flung as Trinidad and Madeira.

Widely accepted by scientists as being native to Central America, maize or corn has cultural, spiritual – sacred and ceremonial – and economic significance for many peoples who are descendant from Mesoamerican cultures. It is suggested that indigenous Americans domesticated this wild grass teosinte, belonging to the genus Zea, some 10,000 years ago. Corn or maize, also referred as ‘yellow gold’ by the early European colonisers, became an important commodity during the age of empire when Europeans colonised the Americas in the late 15th century. And as the geographical reach of colonial institutions and trade grew over the centuries so too did the spread of this particular crop introducing them to many of their colonised territories to increase yields and therefore profit. This was the route through which corn came to be introduced on island of Madeira.

Madeira or more appropriately the Madeiran archipelago is an autonomous region of Portugal in the Atlantic ocean off the coast of north west Africa. Portuguese explorers claimed the archipelago in the name of Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal in 1419 and began settling the islands from 1420 onwards. These settlers were initially made up of Portuguese colonial officers, nobility, merchant shipmen as well as prisoners and slaves, mostly from Africa, and later on by the British, German, Genoese, Polish and the French to name but a few. The islands are the result of volcanic activity some 66 million years ago, naturally mountainous and rocky with rich soil and a subtropical climate that makes it pleasantly spring-like year-round. For the European settlers on this island, the slaves were instrumental and essential to taming this wild landscape – clearing entire forests (doesn’t sound like biodiversity was a priority at the time!) with some suggestions that it might have taken up to a decade to clear them all, digging irrigation canals (these are called Levadas), terracing the land often on steep slopes, and cultivating the land – basically doing all the hard work!

Although corn was introduced to Madeira by the Portuguese in 1790, it was not the most profitable crop to have been cultivated there. That claim goes first to wheat, then sugarcane and by the 18th century it was the fortified wine that was made on this island – Madeira wine – that the island became most synonymous with. In a way the changing agricultural landscape of Madeira paints a picture of the European colonial trade and what was in demand and what was not. So, where does corn come in? Actually, the answer might be in the past agricultural landscape of the island itself. The more profitable and productive vines for growing the grapes that are eventually fermented into the fortified wines are more often than not grown on the steep slopes to maximise their quality whereas the low-lying areas were used for growing corn, wheat, rye and barley and the areas closer to sea level for growing tropical and Mediterranean fruits. Given this, it is highly likely that corn was cultivated for local consumption as opposed to export and significantly, for consumption by the labouring classes, many of whom would have been former slaves as slavery was abolished in Madeira in 1775, grown on small holdings dotted around their humble dwellings.

One of the examples shown here is of a stalk of corn that was collected on Blandys quinta (‘quinta’ possibly referring to an estate or a farm, but sometimes also signifying a villa and ‘Blandys’ presumably being the owners) in March 1842 on the island of Madeira. The only other data included is the scientific name – ‘Zea mays’. That is all the information that can be gleaned from a glance at that sheet. It does not give the name of the collector, the reason it was collected, who grew that corn, what was it used for, by who and so on and so forth. It is sometimes staggering to realise that by simply looking at that innocuous sheet of antique paper on which the stalk is mounted with only those scant bits of information that how much was actually left out rather than included! The rest has been put together through meticulous research to give an idea of the bigger picture in order to increase our understanding of where such specimens which make up the collections at Leeds comes from, their history and the stories behind them. I think that this is as important as the scientific information about its classification and taxonomy as it is about giving credit where it belongs – attribution. As my colleague Rebecca Machin has stressed in an earlier blog about the importance of attribution in science, here’s to those whose efforts have not been recognised and recorded so far!

One down many more to go.

By Rathi Tamilselvan, 'Rooted in History' project placement

Read Rathi's first blog, Rooted in History.