Rooted in History

Leeds Museums and Galleries is home to a of tens of thousands of dried plant specimens whose geographical reach spans from the American Rockies to New Zealand covering a diverse range of vascular plants, mosses, lichens, and fungi to name but a few. Much of the museum’s botanical collections were supposed to have been lost as a result of the bombing in 1941, and subsequently, due to the lack of adequate storage facilities for such delicate material. The result being that much of Leeds’s current botanical collections were acquired during the latter part of the 20th century. This is not to imply that the current collections all date from the 20th century. Starting almost from scratch after the bombing allowed Leeds Museums and Galleries to acquire an eclectic mix of botanical collections – from Ida Roper’s herbarium to the Welcome Institute’s plant collection and from the Leeds Naturalists Club to those belonging to the Bankfield Museum (Calderdale Museums Service) focussing on Leeds and the Yorkshire region.

The practice of collecting plants for the purposes of study – medicinal and agronomy – or even recreation can be traced back thousands of years. Many of the ancient civilizations like the Egyptians, the Chinese and those from the Indus Valley have been known to have widely practiced the custom of collecting and preserving plant specimens for such purposes. The term ‘herbarium’, which has its roots in Latin, marks a collection of dried plants that have been preserved and mounted (hopefully on acid-free paper!) to retain as much of its characteristics as possible for scientific purposes. Sometimes this meant preserving an entire plant – from roots to seeds – but most often only certain segments that were considered of interest and therefore worth studying. In Europe, during the middle ages, the term ‘herbarium’ did not have the same connotations as it does today It was used to refer to botanical treatises featuring illustrations of the plants under discussion. Instead, it was the term ‘hortus siccus’ – literally meaning ‘dry garden’ – that meant what we now widely refer to as herbarium. This shift in terminology happened around the same time as the body of knowledge known as Natural Sciences came into its own during the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe.

It was a time when European intellectuals believed that to fully understand the natural universe, a hands-on approach was the only way to transform our understanding of it. It led to the creation of a public culture in 18th century Europe that was extremely scientific-oriented where everything needed to be observed, sorted and classified. Many Learned Societies that were formed during this period, be they experts or amateurs or a combination of both – the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society, the precursor to Leeds Museums and Galleries, was one such institution – owe their existence to this new scientific way of thinking. It was extremely fashionable, not to mention a sign of high culture, to claim membership to such societies.

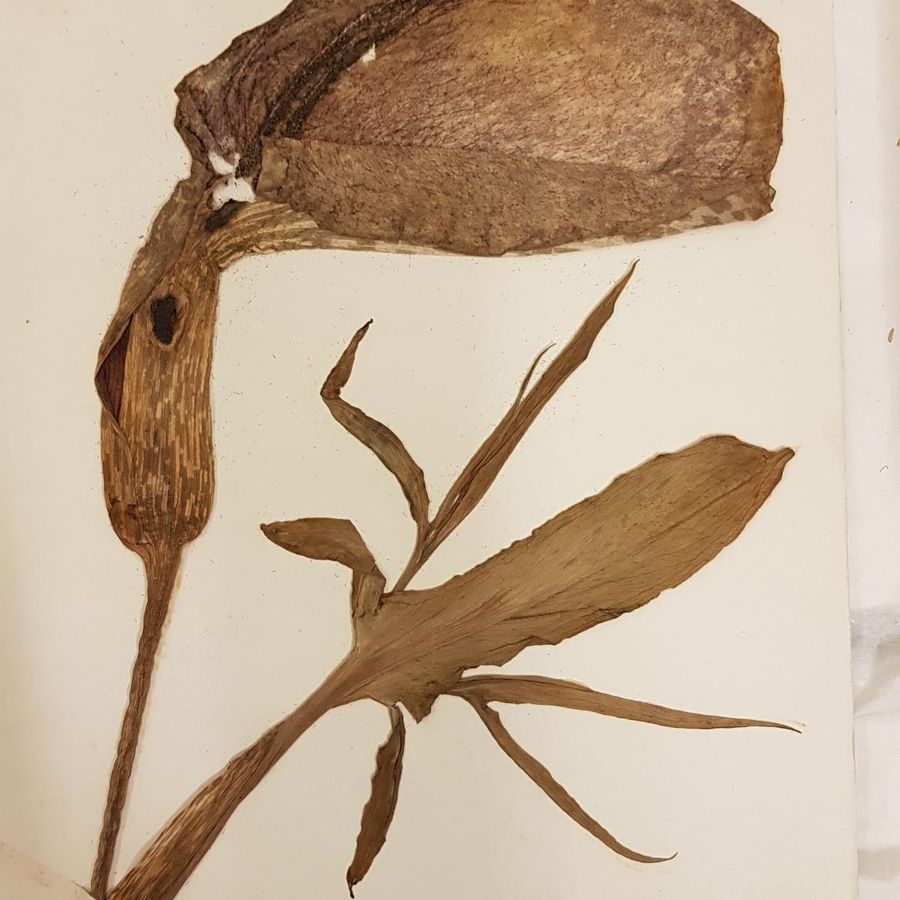

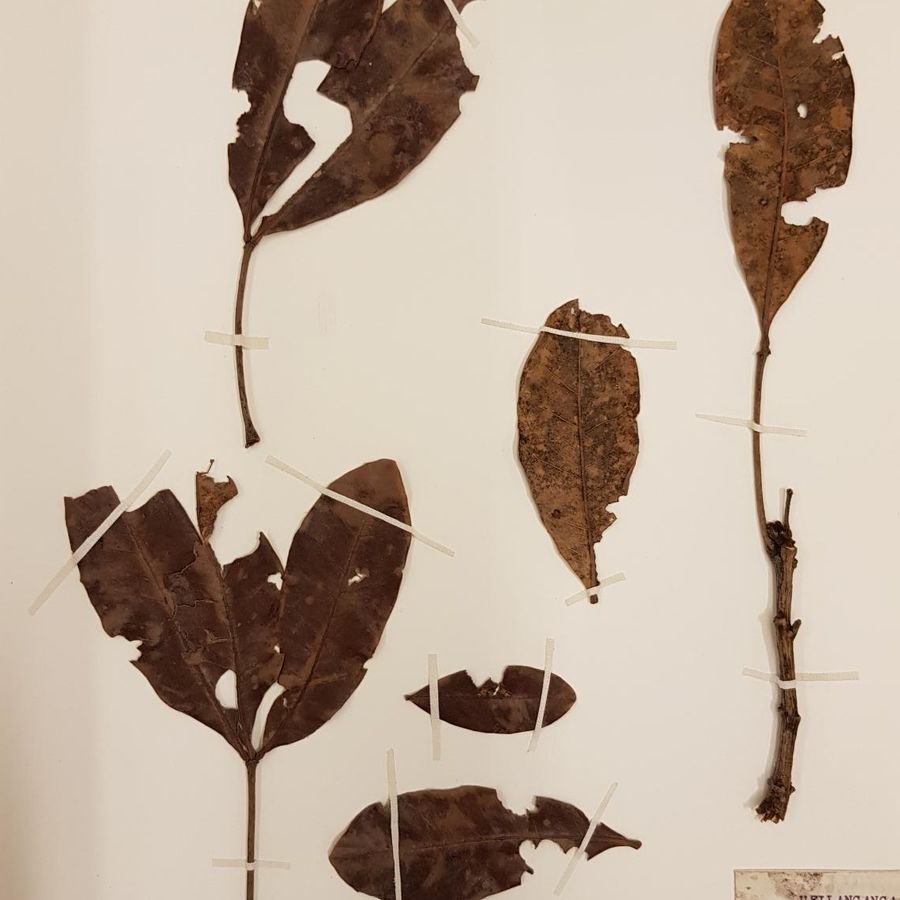

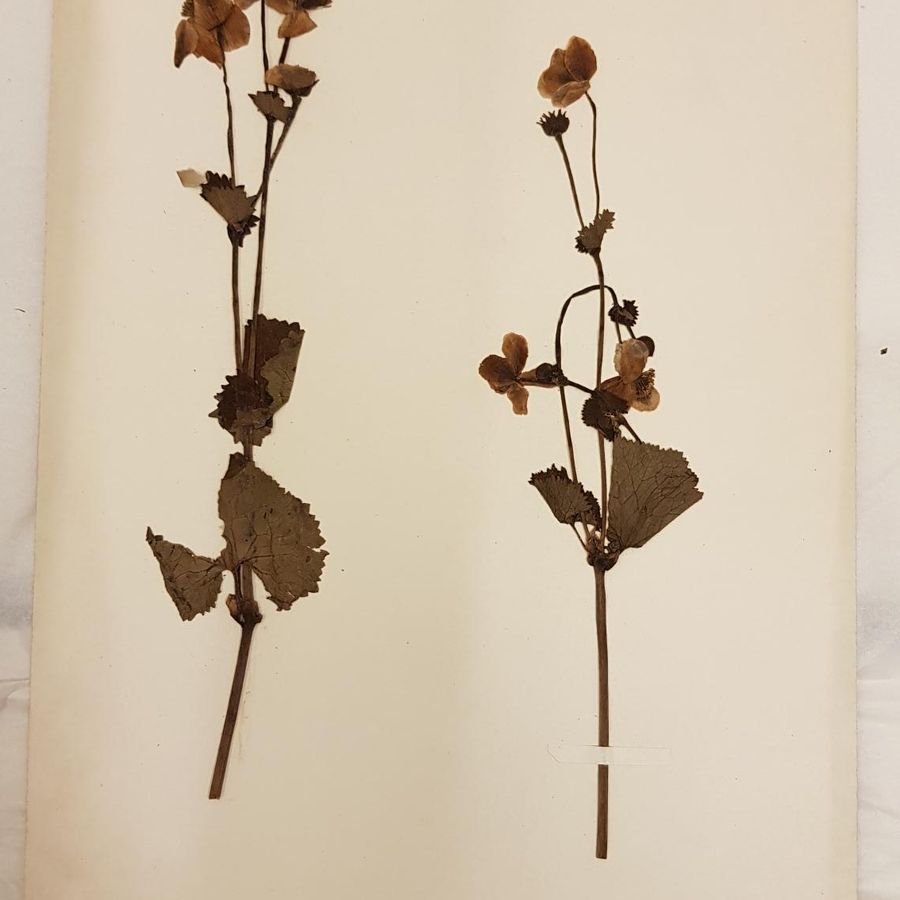

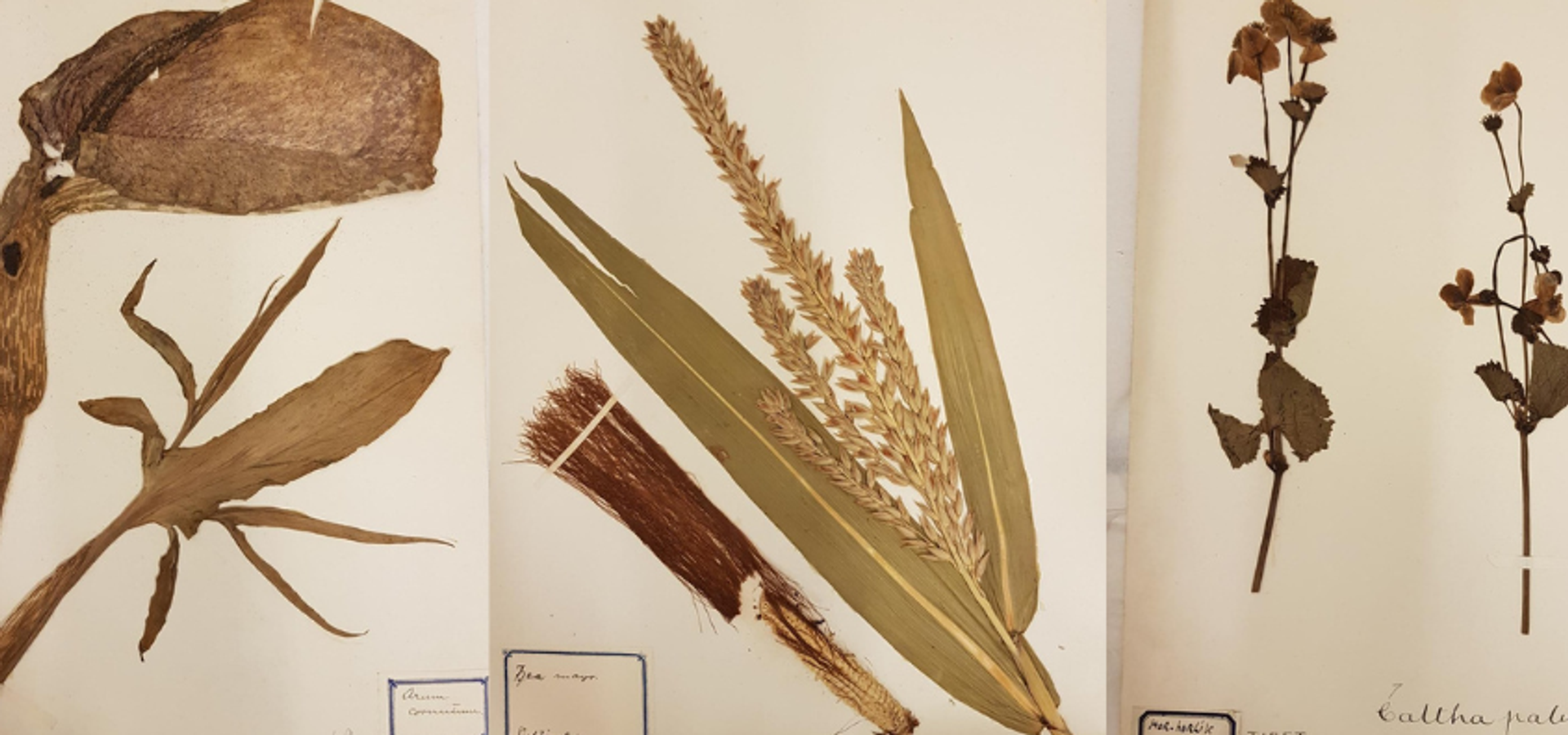

Plants were one such subject that was extremely popular in 18th century Britain. Money was poured into creating the most elaborate gardens with an insatiable appetite for exotic plants which became prized possessions of botanical societies or wealthy collectors, cultivated in hothouses or pressed into dried plant collections. Collecting plants was extremely desirable and, as commodities, were important not only socially, but economically and medicinally. You could even argue that in most cases the boundaries between them were hard to distinguish – much of which is still true today. Plant hunting and exploring as a profession became extremely lucrative not to mention notorious as a result. Many such explorers and hunters (in the name of science!) exploited the colonial reach of the Empires to hunt for these plants from the farthest corners of the globe. And so began the race to see who could hunt down the next exotic plant (fig.1) that was unknown to Europe (I hesitate to use the term discovery here. Is it really ‘discovery’ when it was already known to the indigenous peoples living in many of those lands?); the next maize (fig.2), tea or spice that was to going to line the pockets of the colonial enterprise; or the next medicinal plant that could be tracked down in the jungles of Africa (fig.3) or plateaus of Tibet (fig.4).

Consequently, Leeds’s plant collection is a product of these developments and is its microcosmic reflection. As a work placement on the project Rooted in History, I now have the opportunity to research, document and record information on some of these plant specimens and collections that make up these historical herbaria; to tease out the stories of the people, places and plants that now call Leeds home.

By Rathi Tamilselvan, 'Rooted in History' project placement