Let’s Talk About Segs

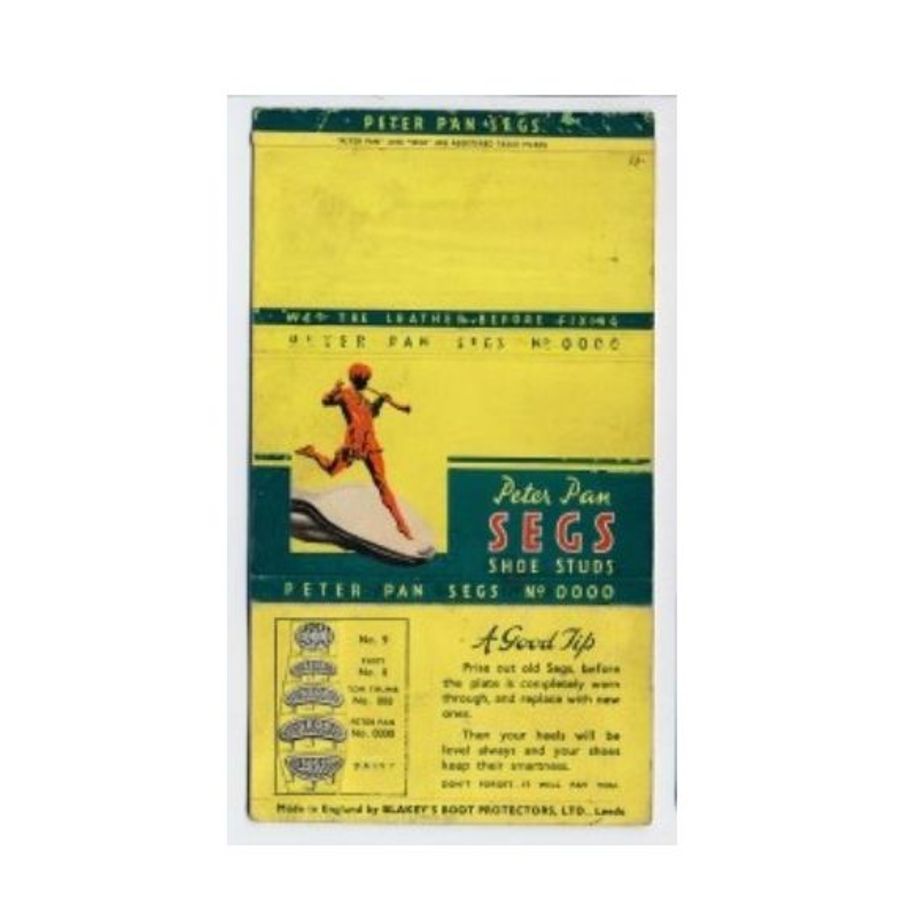

That’s right, segs. Alternatively known as hobs, heels, studs, shoe plates, toe-tips, shoe-protectors, boot-protectors – and to give them their Sunday name – segment of steel. Made in Leeds for over a century to make your shoes and boots keep on running, they continue to add a glint of style to footwear today.

Blakey’s shoe and boot protectors were invented in 1880 by Keighley-born bright spark John Blakey, an individual who had previously taken shuffling steps towards his big invention with a range of shoe-related innovations. The company myth-making machine would have us believe that Blakey literally stepped on the idea. Hiking out on the moors one day – so the legend goes – he got a piece of metal stuck in his boot sole. On inspection, he found that the tread had worn on every part of the boot except the area where the stray metal had lodged itself. Eureka!

If we want to be picky about it, segs were the lighter-weight studs aimed at those stepping out in fashionable shoes. However, I’ll be using ‘segs’ as a convenient shorthand for all of the Blakey products.

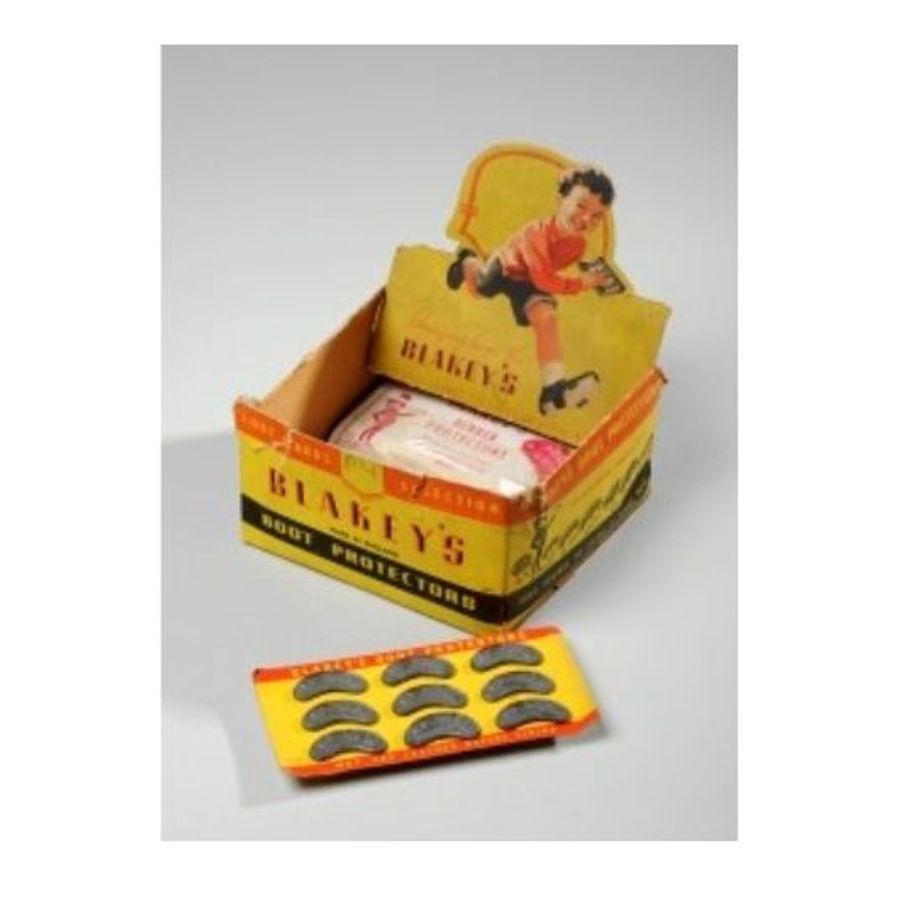

Limited incomes at the time meant that recycling was a way of life for many. Blakey’s segs were an ingenious way of extending shoe life for those on modest budgets. This Leeds product has seen over 140 of service in a vast range of applications from working boots to stiletto heels. Blakey’s segs were to last the test of time and even enjoy a revival recently amongst well-heeled mods and today’s hipsters and tweedies.

At Leeds Museums & Galleries we have an amazingly rich collection of Blakey’s shoe-saving products. We also look after a fascinating archive of advertising illustrations that helped make this humble Leeds product a household name across the globe.

The Blakey’s factory was located in the Armley district of Leeds and was notorious for distributing a hideous odour throughout the district. The factory, set cheek by jowl with densely-packed working class streets, also had its own direct rail link for receiving raw materials and distributing finished goods.

With a product as simple as theirs Blakey’s quickly realised that brand recognition was vital. Therefore, they devoted considerable energy to developing marketing campaigns trumpeting the quality of their protectors over competitors’ ‘inferior’ offerings. While we don’t know the identity of the artist who created the many illustrations and design schemes used by the company, we can be sure that they were given plenty of creative leeway.

Many of the proofs in our collection bear handwritten comments (presumably by a Blakey’s marketing executive) suggesting tweaks that would ensure the brand would get noticed. In their advertising Blakeys wore their pride in their products like a suit of armour, warning consumers against opting for cheaper imitations, “Don’t believe the tales which the manufacturers of cheap goods always tell – that you are paying too much.” Someone in the marketing department was clearly on fire that day, as they continue, “The laws of trade are as unalterable as the laws on nature. Don’t break your head in trying experiments against them.”

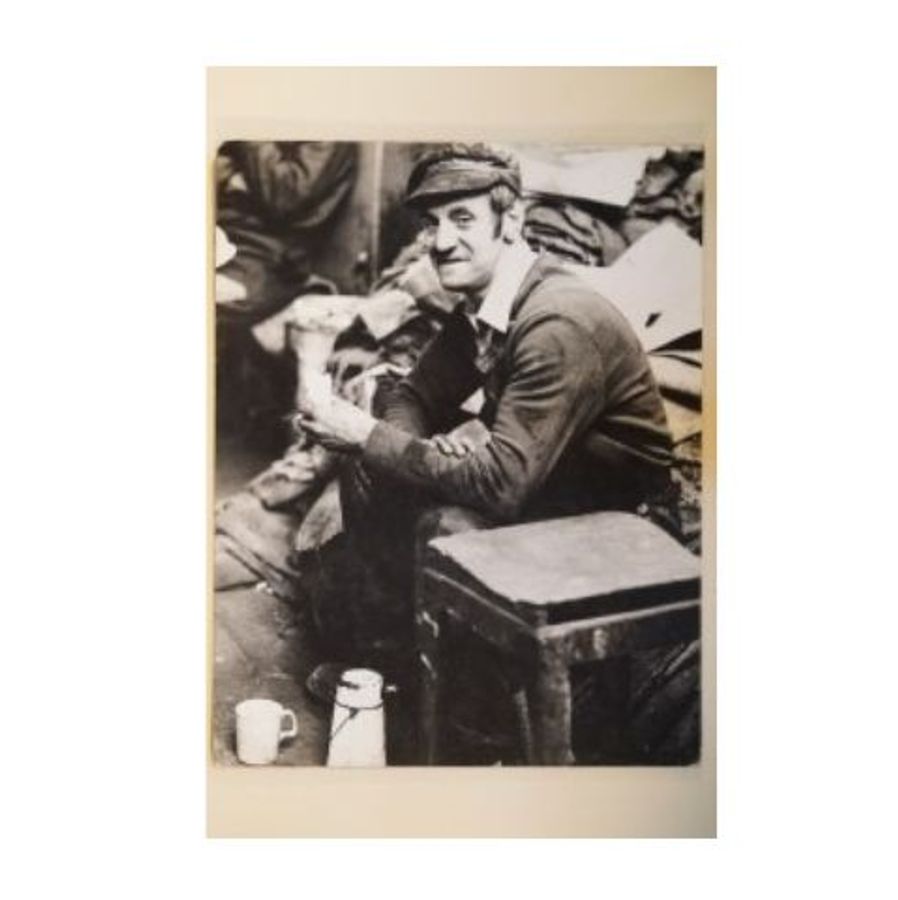

Gazza, who worked for Blakey’s in the mid-1970s, recalls the process of creating castings for segs:

“I had to ‘knock off’ the segs from the metal frame that they were attached to. The moulds were made by a machine called a ‘Disa’ (Disamatic moulding machine), which would compress sand into a shape like an Airfix model with branches leading to the shape of a seg. The metal was still hot from the sand moulds. We had to knock them into metal tubs and when they were full we would drag them and load them onto trolleys to be taken to the warehouse . . . It was extremely dangerous work with no safety clothing except a leather apron and steel toe-capped boots. I would go home every afternoon at 5pm absolutely shattered.”

The spartan conditions for workers at Blakey’s casting department were captured in Derek Lee’s poem Tea Break at Blakey’s:

At first the endless bike ride through the fog

to punch the foundry clock at seven thirty;

and there we mustered, shivering and spitting,

stamping our feet like broken marionettes.

Then we forgot the January cold,

among the dirt and fumes and burning steel.

Despite the basic working conditions faced by some of their workers, Blakey’s do appear to have been reasonably caring employers. Welfare activities included a swimming club for staff members and their families, an annual Christmas club and the introduction of a modern staff canteen in the 1960s.

As late as 1994 Blakey’s segs could be found in 42 countries worldwide. Of these, Nigeria was the largest market. The catastrophic collapse of the country’s Naira currency, however, cost the Armley firm over £100,000 of business.

Goodwins of Walsall in the West Midlands bought the Blakey’s brand in 2014 and continue to protect the nation’s soles. Part of the old Blakey’s works still survive on Modder Avenue. If you stand still long enough to squint up at the fading ghost sign, it is still possible to make out the painted legend on the crumbling brickwork, ‘Armley Malleable Ironworks’.

By John McGoldrick, Curator of Industrial History. Gazza’s memory of creating castings was referenced from the Do You Remember website. Derek Lee’s Tea Break at Blakey’s is from Manchester Voices, Issue 16, Winter 1977/78.

27 May 2020