Decolonising our Life On Earth Gallery

Many of the natural science specimens on display at Leeds City Museum were collected from countries that Britain colonised as part of the British Empire. Colonised people were treated badly, including being killed, by colonising powers, including Britain and other European countries (colonising means taking control of a country, often to use its resources and people, to gain money and power). The legacy of the violence of colonialism can be found in many places today, including museum displays. The specimens in our collection did not arrive in Leeds by chance. Many were collected by people who remain unacknowledged on specimen labels or exhibition text. More about how the violence in colonialism affected our natural science collections can be found in the Journal of Natural Science Collections.

Decolonising collections can involve several approaches, including being honest about where specimens were collected from; acknowledging the work of unnamed collectors; sharing information about the violence or exploitative treatment of colonisers involved in collecting; and reinstating indigenous names for plants, animals and locations. The best place to start to find out more about this subject is this article by Miranda Lowe, a curator at the Natural History Museum in London, and Subhadra Das.

Decolonisation of our collections was something that had concerned me, and my fellow natural science curator Clare Brown, for some time. We had both researched the colonial history of specimens on display in the past, such as the popular Leeds Tiger, and Mo Koundje the gorilla. When we were given the opportunity to reinterpret the Life on Earth gallery, we both felt it would be a good chance to share more about the colonial history of our collections with the public, as other museums are doing. At the entrance to the Life on Earth gallery, we have displayed a text panel introducing the concepts of colonisation and decolonising our collections to our visitors.

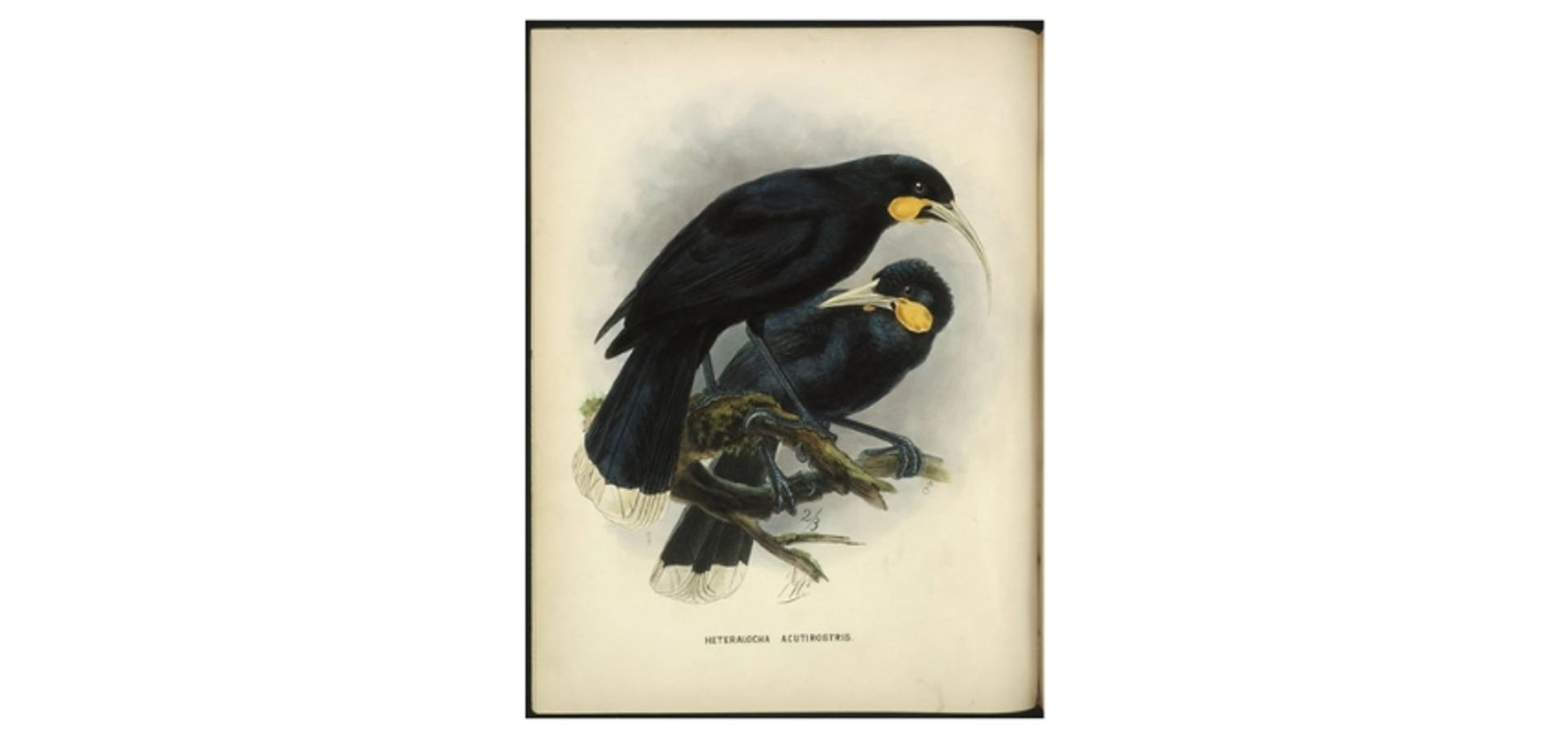

We wanted to highlight some of the ways that colonialism affected nature, and our collections, through telling the stories of some of our specimens on display: a Western Lowland Gorilla (‘Mo Koundje’ or ‘Mok’), a Bengal Tiger (the ‘Leeds Tiger’), a Giant Panda (‘Grandma’), a Yak, and a Huia. Each of these animals has their own story, or a story linked to their species, which tells us something about colonialism. As these are quite complex, we displayed this information in banners alongside each specimen, but separate from other labels. Each banner has a QR code, which links to further information about the specimens, including audio recordings of interviews. For example, a QR code on the banner beside Mok, our Western Lowland Gorilla, links to more information about how it came to be in our collection.

As well as adding deeper information about chosen specimens, we were also mindful of decolonising our language throughout the gallery. For example, the new label for a Huia says that it was from ‘Aotearoa (New Zealand)’, prioritising the indigenous name for its country, which had been replaced by its colonisers. We also felt it was appropriate to acknowledge that colonisers also killed Māori to take their land and resources, as well as impacting Aotearoa’s native wildlife.

We hope that our visitors will learn more about our natural science collection through including more information about its colonial history in the Life on Earth gallery. The legacies of colonialism in many countries are still felt today in nature conservation, affecting the survival of endangered species, as well as the daily lives of people who live with and near them.

By Rebecca Machin, Former Curator of Natural Sciences at Leeds Museums and Galleries.