Welcome to the Life on Earth Gallery

There are QR codes around the gallery that look like the one you just scanned. Many mobile phones can scan them by taking a photo using the camera function.

Scan the codes to find out more about the objects we have on display and Leeds’s collection of natural history.

None of the codes automatically play sound when you scan them. Some have things to click on to listen to once you have scanned them.

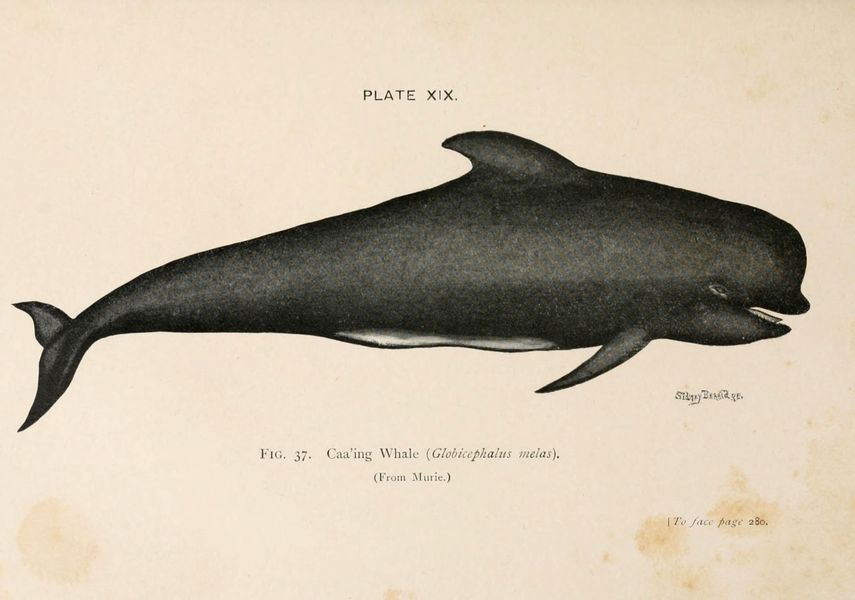

Long-finned Pilot Whale

Above you is the skeleton of a Long-finned Pilot Whale.

Our whale has a sad story. In 1867, it was in a pod of around 200 whales, swimming around Scotland. Several boats drove them into shallow water.

The whales were killed with harpoons, spades and guns. Our whale has a hole in its skull with lead inside, so was probably shot.

Our whale was killed when Britain still had a whaling industry. Whales were hunted for their meat and oil, which was used for street-lighting and in industry. Some species were almost hunted to extinction.

In 1982, the International Whaling Commission banned the commercial hunting of whales. This was a rare example of the world coming together to protect nature. Unfortunately, pollution, plastic waste, and fishing nets still threaten whales and other sea life.

For over 1000 years, it has been traditional in the Faroe Islands to drive pods of Long-finned Pilot Whales towards land, to kill them for food. This was a good source of protein in the past, and the meat was shared by the whole community.

The hunting continues today, and some Faroese people feel it is an important part of their culture. Many people think whale hunting is cruel and needless. Pollution means that Long-finned Pilot Whale meat now contains dangerous levels of poisonous chemicals.

Whales form an important part of human culture, inspiring beliefs, art and stories around the world. We can help whales by reducing the amount of plastic we use, and the pollution we put into the sea.

Whale poem

Winston Plowes was commissioned to write a poem for the installation of the whale at Leeds City Museum in 2019. The poem was written in ghazal style. This is an ancient form of poetry where each couplet, or two lines of the poem, talk about the poem’s theme in a different way. The second line of each couplet also has a repeated phrase; in this case it is ‘my song’.

The Seven Seas charting my song.

Hear the journeys within my song.

My fin has cut the ocean’s skin

Seabirds’ calls mimicking my song.

Call me blackfish call me sea ghost

Bubbles perforating my song.

Sing your name and I’ll sing mine back

Clicks of time echoing my song.

Like a brush that paints through water

Charcoal black skin tracing my song.

Slipping through a vast blue desert

Deep dark below weaving my song.

In the cathedral of my bones

Imagine lungs singing my song.

Deep shadows in shallow waters

The river strangling my song.

Stranded with my family pod

Gunshot and knife ending my song.

Winston Plowes

Plastic

There are lots of things you can do to help reduce the amount of plastic in the sea. One of the most rewarding is to pick up plastic as you walk down the beach. You can do it yourself or join an organised beach clean.

All the organisations linked to below run group beach cleans you can go along to:

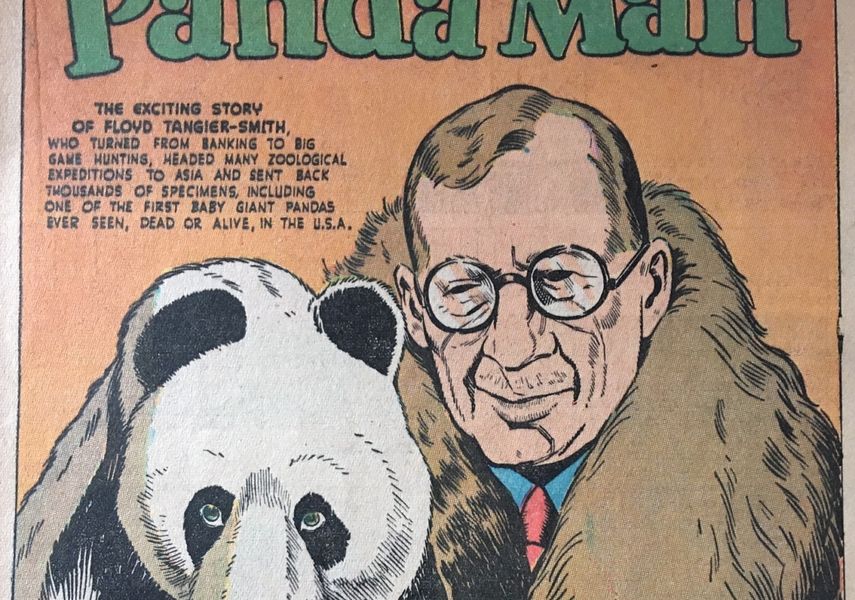

Giant Panda

This Giant Panda once lived near Weizhou village, close to Chengdu in central China.

Why is there a Giant Panda in the museum?

Floyd Tangier Smith was an American working in Shanghai. In 1938, looking for adventure, fame and money, he went to central China to catch Giant Pandas. Smith employed local hunters to catch them. We don’t know anything about the hunters. They caught six pandas, but one died shortly after.

At the time, China let Smith catch and export Giant Pandas, but soon after, the practice was stopped.

Smith shipped the surviving Giant Pandas to the UK, where London Zoo was keen to buy one. They were the first Giant Pandas to arrive in the UK.

This panda was named ‘Grandma’ because she was older than the others. After she died, she was bought by Leeds Museums and Galleries.

The scientific name for a Giant Panda is: Ailuropoda melanoleuca

Creating Change

Talking to decision-makers about what’s important to you can be very effective.

Who should I speak to about my views?

If you live in Leeds you will be represented by a local councillor. These are people who are voted for by the people in your area to represent your views at Leeds City Council. Find out who your local councillor is by clicking on the button below.

The council make decisions about how to run the city – like where to put in bike lanes and how to run the city’s museums. Find out more about how the Council works by clicking the button below.

How does Leeds City Council work?

You can also speak to your Member of Parliament (MP). These are people who represent your views to the UK government in London. Find out who your MP is by clicking the button below.

What’s the most effective way of getting my view across?

- Be clear and short. Keep to the point.

- Ask friends, family and neighbours about their views. Record their views and encourage them to get in touch with their councillors too,

- Follow up. Once you’ve had a chat to someone, don’t leave it there. Go back to them to see what action is being taken.

Climate Emergency

In 2019, Leeds declared a climate emergency. Use the button below to find out more about what this means.

Coltan Mining

What have gorillas and mobile phones got in common?

Gorillas live in forests growing on soil that contain an ore called Coltan. An element called “tantalum” can be extracted from this ore and mobile phones need tantalum to work. Tantalum is very, very rare and sadly gorilla habitat is often mined to extract it.

You can help reduce the need for new tantalum by recycling your old mobile phone. There are lots of places that will help you do this, including the two organisations linked to below:

Deforestation

Palm oil

Orangutans live in the rainforests of Indonesia and Malaysia. They spend their lives in the trees, eating leaves and fruit. They need large areas of forest to feed in and to breed. Huge areas of Orangutan habitat have been, and continue to be, burnt or logged to clear space for palm oil plantations.

You can help

Palm oil is an ingredient in lots of packaged and processed foods, and in cosmetics. It is not easy to avoid buying palm oil, and some palm oil supports people’s livelihoods. The most helpful thing to do is to choose palm oil that is produced sustainably.

Look out for RSPO-certified products, approved by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil.

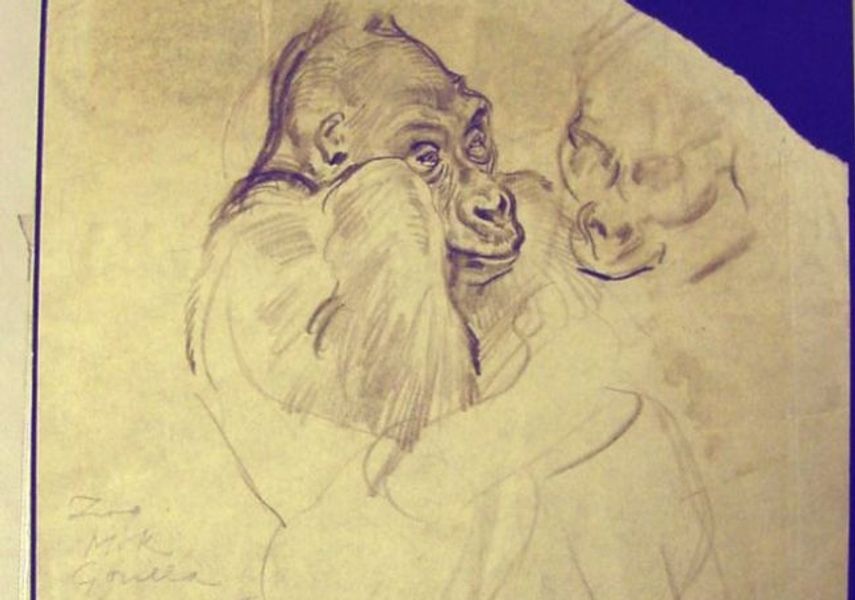

Why is this Congolese gorilla in the museum?

Britain, France, Belgium and other European countries once colonised large parts of Africa. This gorilla lived in what is now called Congo, or the Republic of the Congo. At the time, it was a French colony known as the French Congo. This is to the east of the much larger Democratic Republic of the Congo, which was colonised by Belgium and then known as the Belgian Congo.

When the gorilla was young, he was kept as a pet by a French man called Jean Charles André Capagorry. Capagorry was a colonial administrator, helping to run the colony for the French government. The gorilla was called Mo Koundje. He was kept with a female gorilla called Moina Massa.

We don’t know where Capagorry got the gorillas from, but he kept them as pets for around two years. When they got larger and more difficult to handle, he took them to France, and from there sold them to London Zoo in 1932. He was paid £1100, which is equivalent to around £75,000 today. The gorillas’ exact ages are not clear, but Mo Koundje was probably around five years old, and Moina Massa around seven.

The Gorilla Trade

It was against the law to keep gorillas as pets, and to export them from Africa, without a special permit. Despite this, Capagorry and other European colonists were able to make money by selling gorillas to European and American zoos. Congolese people would have been jailed for doing this.

To capture young gorillas, hundreds of people would surround a family of gorillas with netting, and remove trees until they had no cover. The adults would be speared to death, and the young gorillas captured. The African people hired to do this work were poorly paid and put themselves in a lot of danger.

Unfortunately, gorillas are still at risk from the illegal pet trade and bush meat trade. Sanctuaries based in Africa provide rescued gorillas with safe homes.

What do you think?

Mo Koundje died in 1938, from kidney disease. Leeds Museums and Galleries bought his skin and skeleton from London Zoo. We also have other gorilla remains in our collection, which all help us to learn about gorillas, and to tell gorillas’ stories. Museums in Europe and North American have hundreds of gorilla specimens in their collections, used for scientific research and education.

In contrast, there are very few gorilla specimens stored in Africa. There are none on public display in museums in countries where gorillas live. This imbalance is a small part of the legacy of Europe’s colonial past in Africa.

The scientific name for a Western Lowland Gorilla is: Gorilla gorilla gorilla (That’s an easy one to remember!)

Huia

What are Huias?

Huias are extinct birds once found in the forests of Aotearoa New Zealand.

They are sacred to Māori people; their tail feathers are used only by those with great mana (status and power). Huias are unusual because the male and female have different shaped beaks.

How Huias became extinct

The last record of a living Huia was in 1907.

Whole specimens were bought by Western collectors in the late 1800s, and their beaks and feathers were bought by hat and jewellery makers. The Duke of York visited in 1901 and was given a Huia feather to wear in his hat. The feathers became so sought after that, only a few years later, Huias were declared extinct.

Huias in Māori culture

Huias were recognised as a sacred bird by the Māori long before they were prized by Western collectors.

The extinction of a species is always a terrible loss to the world, and the extinction of the Huia is a deep wound in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Why do you have these Huias at the museum?

John H. Hirst (1888-1963) was a stuffed-bird enthusiast from Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire. He would have spent hundreds of pounds putting together his collection. His son gave the collection to the museum in 1964. This pair of Huias were part of it.

The scientific name for a Huia is: Heteralocha acutirostris

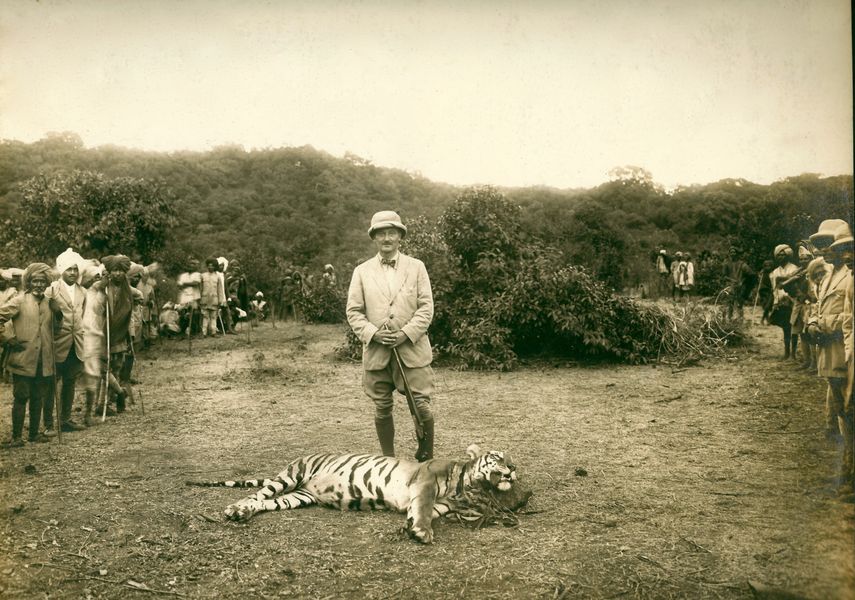

Tiger

Why is this tiger in the museum?

This tiger once lived in the Deyrah Dhoon valley in northern India.

Sadly, in March 1860, a man called Charles Reid shot him and had his skin shipped to the UK. He was one of the largest tigers ever killed.

His skin was displayed in the 1862 International Exhibition in London.

He was then purchased and stuffed by a London taxidermist, and finally bought by the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society. He has been on display in Leeds since 1862.

Charles Reid hunting tigers in Deyrah Dhoon

Reid was a British army officer, working in India as part of the British Empire. Tiger hunts were a common hobby at the time and Reid took part in them. Many British army officers thought that they were providing a service to local people by killing a terrifying pest.

Reid wrote to a friend about this tiger:

‘I had a tiger in the Exhibition of 1862, and which is now in the museum at Leeds, which was the largest tiger I ever killed or ever saw.’

Another officer joined Reid hunting tigers in Deyrah Dhoon and described the place that the tiger grew up in:

“…impenetrable thickets and swampy cane-brakes. [Behind] the irregular line of tree-tops, rose the precipitous slopes and buttresses of the outer-range Himalayas, some three of four miles distant. Rearward, in like manner, the low serrated ridge of the wooded Sewaliks cut the deep sky-line.”

He is writing about how this valley, which is near the Himalayan mountains, is hilly and full of thick grass and weeds.

What do you think?

In 1860, Reid thought hunting tigers was a noble thing to do. ‘Face Him Like a Briton’, was one saying about tiger hunting. One estimate puts the number of tigers killed in central India between 1875 and 1925 at 80,000.

Today, there are only a few thousand tigers left.

Tigers are endangered and have legal protection. Unfortunately, they are still hunted for the illegal sale of their body parts.

In Conversation

Listen to curators Rathi Tamilsevan and Clare Brown discussing the history and future of the tiger at Leeds City Museum. Why is the tiger here? Should it be here and how should it be displayed?

Click the play button to hear their conversation.