News from the Past: September

In this new series created by our volunteer Mel Kerry they look back on the past with this feature of newspapers, clippings and other ephemera from the Leeds Museums and Galleries collection and explore what news looked like in our cities past. September’s edition features a revolutionary’s call, the Leeds Town Hall, and a Russian army’s fall.

Berthold’s Political Handkerchief

In the 1830s, just before the reign of Queen Victoria, the Industrial Revolution was in full swing and so were political tensions and disagreements. Working conditions in factories were dangerous, only the upper class men had the right to vote, and some industrial city's like Manchester and Birmingham were not represented in parliament. Many people started to protest against this unfair and unequal government treatment.

One of these protestors was Henry Berthold, a radical journalist and the leader of the National Union of Working Classes. He disagreed with the government tax on newspapers, describing it as a “tax for our knowledge.” Starting on September 5th 1831, Berthold printed ten issues of his own newspaper on cotton instead of paper to avoid the tax and to spread knowledge to the working class. A paragraph from the first edition reads:

“To the Boys of Lancashire. We have no patent for this new pocket handkerchief, because we intend to advocate the interest of the working people, and consequently do not intend to pay any tax for our knowledge to the tyranny that oppresses us.”

At the time, it was against the law to publish seditious libel (hatred or criticism of the monarchy or government) in a newspaper. Henry Berthold would later be convicted for shop-lifting in 1833 and transported to Australia as punishment.

Admission Ticket to the Town Hall

In the mid-19th century, Leeds was rapidly growing, putting itself on the map as a major industrial town of the Victorian era. With this new power and success came the construction and establishment of the Leeds Town Hall.

Its construction took place between 1853 and 1858, following classical Roman-inspired designs by the contest-winning architect Cuthbert Brodrick. Many features would only be added during construction, including the signature baroque clock tower. Brodrick later designed several more of Leeds’ most iconic buildings, including the Mechanics Institute, the present location of the Leeds City Museum, where the Brodrick Hall is named after him.

This admission ticket is dated to the 7th of September 1858, the day when the Town Hall was officially opened by Queen Victoria. The Queen’s arrival in Leeds attracted crowds of over 400,000 people, including local reporters, country-wide police reinforcements, and over 20,000 schoolchildren singing hymns on Woodhouse Moor. The city was decorated with flags and banners for the occasion.

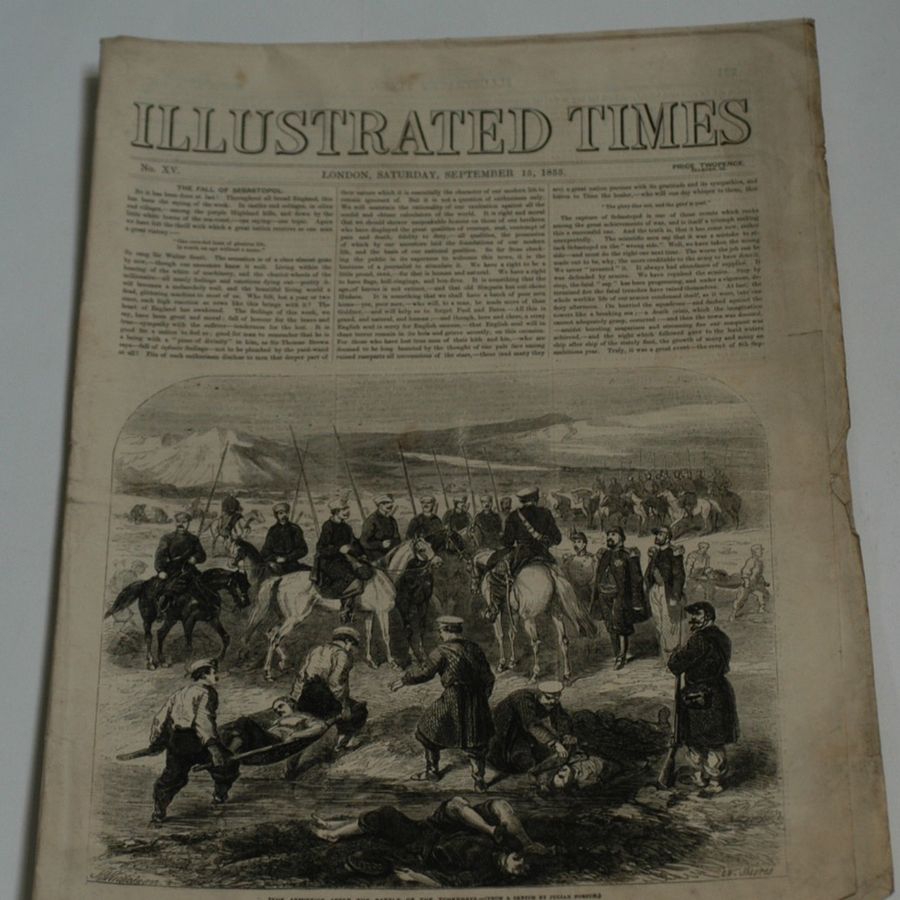

The Fall of Sebastopol

Between 1853 and 1856, many British men went to Crimea to fight in the Crimean War. Britain, France and Sardinia allied with the Ottoman Empire to fight against the Russian forces, who were trying to invade Eastern European territories controlled by the Ottomans.

As the allied forces (Britain, France, Ottoman and Sardinia) were fighting for control of Sevastopol (the capital of the Crimean Peninsula), the Russians launched an attack on the French forces positioned on the Chernaya River. The Russian commander Gorchakov lead an army of over 50,000 men to attack, but the French and Sardinian soldiers held their higher ground with their greater experience and firepower. After 8000 Russian casualties, Gorchakov ordered his men to retreat.

The front page of this 1855 newspaper shows an illustration of the armistice (peace agreement) after the battle of the Tchernaya, featuring men tending to the wounded and uniformed soldiers on horses. The article “The Fall of Sebastopol” honours the “great victory” with the quote: “One crowded hour of glorious life, Is worth an age without a name,” attributed to Sir Walter Scott.